Oxycodone Addiction: Definition, Symptoms, Causes, Side Effects, and Treatment

Oxycodone is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic used to treat moderate to severe pain. It works by binding to opioid receptors in the central nervous system, reducing pain perception and activating reward pathways. [1]

Key Takeaways

-

Oxycodone addiction often begins with legitimate pain relief, then progresses through tolerance and physical dependence into compulsive use when the brain adapts to repeated opioid exposure.

-

Addiction is not a moral failing or lack of willpower — it results from biological changes in the brain combined with psychological stressors and environmental factors.

-

Evidence-based treatment, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT), counseling, and structured support, can stabilize recovery and significantly reduce overdose risk.

In many cases, oxycodone is first introduced after surgery, injury, or chronic pain when relief feels not only physical but also emotional.

Over time, the nervous system adapts, requiring higher doses for the same effect. What begins as symptom management can quietly shift into dependence, leaving patients fearful of pain, withdrawal, or losing control of their medication use.

Families and patients often feel confused or frightened by how quickly this transition can occur — especially when the medication was prescribed by a trusted clinician.

Understanding what oxycodone addiction is, how to recognize warning signs, and what effective treatment looks like is critical for reducing harm and restoring stability.

What Is Oxycodone Addiction? (Quick Definition)

Oxycodone is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic used to treat moderate to severe pain.

It works by binding to opioid receptors in the central nervous system, reducing pain perception and activating reward pathways. [1]

-

Tolerance occurs when increasing doses are needed to achieve the same analgesic or euphoric effect.

-

Dependence develops when the body adapts to oxycodone, and withdrawal symptoms appear if use is reduced or stopped.

-

Addiction (opioid use disorder) is marked by compulsive use, loss of control, cravings, and continued use despite physical, psychological, or social harm.

Signs & Symptoms of Oxycodone Addiction

Physical Symptoms

-

Excessive drowsiness or sedation: Oxycodone depresses the central nervous system, causing persistent sleepiness, mental fog, and difficulty staying awake during daily activities. Sedation may fluctuate as tolerance develops, with brief alertness after dosing followed by extreme lethargy. This is especially dangerous because it often occurs alongside slowed breathing, increasing overdose risk.

-

Constricted (pinpoint) pupils: Oxycodone interferes with normal eye muscle control, causing pupils to remain abnormally small regardless of light. This sign becomes more consistent as dependence worsens and, when paired with sedation or mood changes, can indicate ongoing misuse.

-

Nausea, vomiting, and chronic constipation: Oxycodone slows digestive function, leading to nausea early on and long-term constipation with continued use. Abdominal pain, bloating, and laxative dependence are common and often persist even as the drug’s effects diminish.

-

Itching or flushing: Histamine release triggered by oxycodone can cause itching, sweating, and skin flushing, especially after dosing. While often dismissed as minor, recurring itching may signal repeated opioid exposure and escalating use.

-

Slowed or shallow breathing: Oxycodone suppresses the brain’s breathing drive, leading to slow or irregular respiration. This effect is the leading cause of fatal overdoses, particularly when combined with alcohol or sedatives, and may occur quietly during sleep.

-

Increasing tolerance and withdrawal between doses: Over time, higher or more frequent doses are needed to feel the same effects. Withdrawal symptoms—such as anxiety, sweating, body aches, and nausea—can appear between doses, reinforcing dependence and continued use.

Emotional & Psychological Symptoms

-

Persistent cravings or intrusive thoughts: As addiction develops, oxycodone begins to dominate thinking. Individuals may fixate on the next dose, fear running out, or feel driven to obtain more pills. These cravings reflect changes in brain reward systems—not weak willpower—and gradually crowd out focus on work, relationships, and goals.

-

Mood swings, irritability, anxiety, or depression: Oxycodone disrupts brain chemistry that regulates mood. As levels drop between doses, irritability, anxiety, agitation, or low mood can emerge. Over time, the drug that once seemed calming can intensify emotional instability, reinforcing repeated use.

-

Emotional numbing or loss of interest: Long-term use can dull emotional responses, leaving people feeling flat or disconnected. Activities that once brought joy—hobbies, socializing, family time—may no longer feel rewarding. As pleasure becomes tied to the drug, everyday life feels increasingly empty.

-

Denial or defensiveness about use: When questioned, individuals may minimize their oxycodone use or justify it as necessary. Defensiveness often stems from shame, fear, or difficulty admitting loss of control. This denial is a common psychological defense that allows addiction to continue unnoticed.

Behavioral Symptoms

-

Taking higher doses or using more frequently than prescribed: One of the clearest behavioral signs of addiction is deviating from the prescribed dosing instructions. This may include taking extra pills, shortening the time between doses, or using oxycodone “just in case” rather than for active pain. What often begins as occasional overuse can escalate into routine misuse as tolerance and dependence grow.

-

Using oxycodone for non-pain-related reasons: As addiction develops, oxycodone may be used not only for physical pain but also to cope with stress, anxiety, insomnia, emotional distress, or daily functioning. The drug becomes a tool for emotional regulation rather than medical treatment, signaling a shift from therapeutic use to compulsive reliance.

-

Doctor shopping or obtaining pills from non-medical sources: When prescriptions run out, or providers express concern, some individuals seek multiple doctors, exaggerate symptoms, or turn to friends, family members, or illicit markets for oxycodone. This behavior reflects escalating dependence and often marks a transition from controlled access to increasingly risky and illegal methods of obtaining the drug.

-

Social withdrawal, secrecy, missed responsibilities, or financial strain: Oxycodone addiction frequently disrupts daily life. Individuals may withdraw from social interactions, avoid loved ones, or become secretive about their whereabouts and activities. Missed work, declining performance, unpaid bills, and strained relationships are common as more time, money, and energy are devoted to maintaining access to the drug.

How Common Is It? (Prevalence & Epidemiology)

General prevalence:

In the United States, national survey data show that in 2018, about 1.4 million people (≈0.6 % of the population aged 12 + years) met criteria for dependence on opioid pain relievers (with oxycodone among the most common substances involved). [2]

Clinical settings:

Among adults receiving long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain, estimates suggest that 23.9 %–26.5 % develop some level of prescription opioid use disorder, with 5.2 %–9 .0 % meeting criteria for moderate to severe disorder. [3]

Withdrawal frequency:

In community samples of regular opioid users (people who inject opioids at least monthly), 85 % reported withdrawal symptoms in the past 6 months, with 29 % experiencing withdrawal at least monthly and 35 % weekly or more—highlighting how common withdrawal is among active users. [3]

Causes: Why Does Oxycodone Addiction Happen?

Neurobiology (How Oxycodone Affects the Brain)

Oxycodone exerts its primary effects by binding to mu-opioid receptors in the brain and spinal cord, powerfully dampening pain signals while simultaneously activating the brain’s reward system.

This activation triggers a surge of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, motivation, and reinforcement. Initially, this combination creates not only physical pain relief but also emotional calm, comfort, or even mild euphoria—effects that can feel profoundly stabilizing to someone in distress.

With repeated exposure, however, the brain begins to recalibrate its chemistry. Natural dopamine production becomes blunted, and reward circuits grow less responsive to everyday pleasures such as food, social connection, or achievement.

This process, known as neuroadaptation, drives tolerance—requiring higher or more frequent doses to achieve the same effect. Over time, the brain’s baseline state shifts, and oxycodone is no longer enhancing well-being but merely preventing discomfort.

As dependence develops, the brain increasingly relies on oxycodone to maintain equilibrium. When the drug is absent, stress systems surge, producing withdrawal symptoms and intense cravings. These changes reinforce compulsive drug-seeking behavior, even when the individual is fully aware of the risks or negative consequences.

Genetic & Biological Factors

Biology plays a significant role in determining who is most vulnerable to oxycodone addiction. Research suggests that genetic factors account for approximately 40–60% of addiction risk, influencing how opioids are metabolized, how strongly receptors respond, and how reward pathways are activated. [4] Some individuals experience stronger euphoric or calming effects from oxycodone, making reinforcement more powerful from the outset.

Variations in pain perception and opioid sensitivity also matter. People with heightened pain responses or slower drug metabolism may require higher doses, increasing exposure and risk.

Additionally, co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions—such as chronic pain, depression, anxiety disorders, or PTSD—significantly elevate susceptibility. In these cases, oxycodone may unintentionally treat emotional suffering alongside physical pain, blurring the line between therapeutic use and psychological reliance.

Psychological & Emotional Triggers

Oxycodone addiction often develops in the context of unresolved emotional distress. Chronic stress, trauma, grief, insomnia, or overwhelming life pressures can make the calming and numbing effects of opioids especially appealing.

What begins as legitimate pain management may slowly transform into a way to regulate emotions, escape intrusive thoughts, or simply feel “normal” again.

Over time, the drug becomes a coping mechanism rather than a medication. Emotional discomfort, fatigue, or anxiety can trigger urges to use, even in the absence of physical pain. This learned association strengthens dependence and makes cessation feel psychologically threatening, as individuals may fear facing emotional pain without chemical support.

Environmental & Social Factors

Environmental conditions strongly shape addiction risk. Easy access to opioid prescriptions, especially high-dose or extended-release formulations, increases exposure and lowers perceived danger. Inadequate follow-up care, limited education about dependence, and pressure to quickly return to work after injury can all contribute to prolonged use.

Social isolation, unstable housing, financial strain, and limited access to mental health services further intensify vulnerability. In these contexts, oxycodone may function as both relief and refuge. When support systems are weak, and stressors are constant, the risk of misuse escalates—often silently and gradually.

From Pain Relief to Dependence (Progression)

The progression toward oxycodone addiction is rarely sudden. It often follows a predictable and deceptively subtle path:

Injury or surgery → short-term relief → tolerance → dose escalation → withdrawal symptoms → compulsive use to avoid discomfort.

At this stage, use is no longer driven by pain control or pleasure, but by the need to prevent withdrawal and maintain emotional stability. What once felt like a solution becomes a cycle that is increasingly difficult to escape without structured medical and psychological support.

Who Is Most at Risk of Developing Addiction?

Certain individuals face a significantly higher risk of developing oxycodone addiction due to a combination of biological vulnerability, medical exposure, and life circumstances.

People living with chronic pain or those prescribed opioids for extended periods are especially susceptible, as long-term use increases tolerance and physical dependence, even when medications are taken as directed.

A personal or family history of substance use disorders further elevates risk, reflecting inherited differences in reward processing, impulse control, and stress response.

Individuals with untreated or under-treated mental health conditions—such as depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, or bipolar disorder—are also more vulnerable. In these cases, oxycodone may temporarily ease emotional distress, reinforcing use beyond its intended purpose.

Risk is amplified when patients are prescribed high-dose or long-acting oxycodone formulations, which maintain elevated opioid levels in the body and intensify neurobiological adaptation. Finally, social isolation, unstable living conditions, and high-stress environments—including financial strain or occupational pressure—reduce protective factors and increase reliance on substances for relief or escape.

Side Effects of Oxycodone Addiction

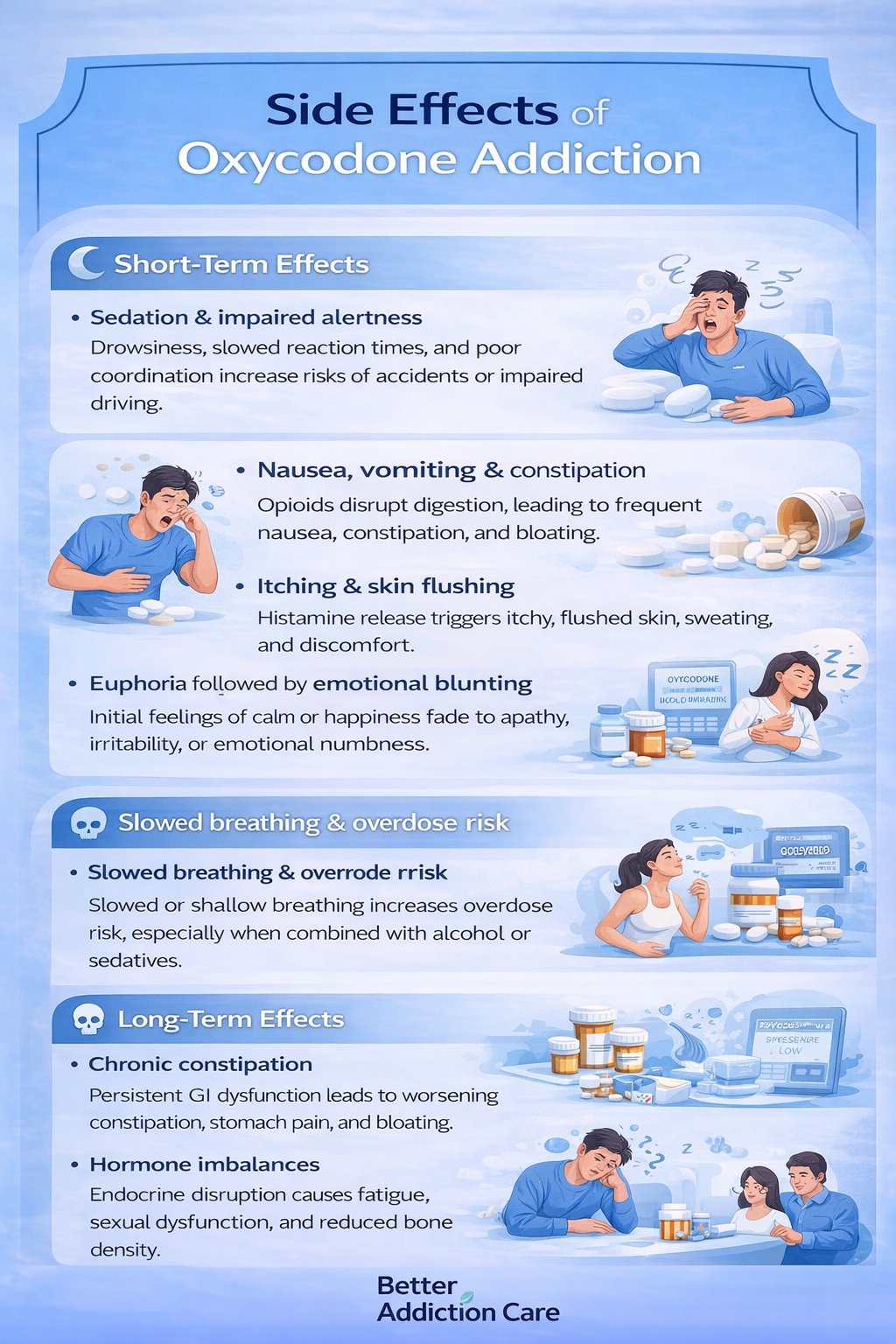

Short-Term Effects

In the early stages of misuse or escalating use, oxycodone can produce a range of noticeable physical and psychological effects. Sedation and impaired alertness are common, increasing the risk of accidents, falls, or impaired driving.

Nausea, vomiting, and constipation frequently occur as opioids disrupt gastrointestinal motility, sometimes leading individuals to use additional medications to counteract these effects. [5]

Many people experience itching or flushing due to histamine release, alongside periods of euphoria that may initially feel calming or emotionally uplifting.

However, this pleasure is often short-lived and followed by emotional blunting, apathy, or irritability. Perhaps most concerning is slowed or shallow breathing, which can occur even at therapeutic doses and becomes increasingly dangerous as tolerance and dosage rise.

Long-Term Effects

With prolonged addiction, the consequences of oxycodone use become more systemic and severe. Chronic gastrointestinal dysfunction can persist, leading to abdominal pain, bloating, and long-term constipation-related complications. Opioids also disrupt the body’s hormonal systems, causing endocrine imbalances that may result in fatigue, sexual dysfunction, menstrual irregularities, and reduced bone density.

Neurologically, long-term use is associated with cognitive slowing, impaired concentration, and mood instability, making daily functioning increasingly difficult.

Paradoxically, many individuals develop opioid-induced hyperalgesia, a condition in which pain sensitivity increases rather than improves, reinforcing continued use. As tolerance escalates, so does the risk of overdose, particularly when oxycodone is combined with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or other sedating substances.

Impact on Daily Life

As addiction progresses, oxycodone use begins to affect nearly every aspect of daily life. Declines in work or academic performance are common, driven by fatigue, impaired focus, or absenteeism. Relationships often become strained, as secrecy, emotional withdrawal, and conflict replace trust and communication.

Financial instability may develop due to medical costs, lost employment, or drug-seeking behaviors, while legal and safety concerns—such as impaired driving or workplace accidents—become more likely. Together, these impacts compound distress and make recovery feel increasingly out of reach without structured support.

Treatment Options

Effective treatment is individualized and combines medical, psychological, and social support rather than relying on detox alone.

Detox / Withdrawal Management

Detox serves as the first step for many patients, helping the body safely eliminate oxycodone while minimizing discomfort.

The setting depends on severity—milder cases may be managed in outpatient clinics, while more severe dependence, co-occurring conditions, or unstable home environments often require inpatient supervision.

Key strategies include:

-

Gradual tapering rather than abrupt cessation to reduce withdrawal intensity and prevent complications. Taper schedules are individualized based on dose, duration, and patient response.

-

Symptom-targeted medications—such as anti-nausea, sleep aids, or non-opioid pain relievers—can alleviate discomfort and improve adherence.

-

Medical monitoring ensures that complications such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, or severe anxiety are promptly addressed.

Detox is not a standalone solution, but it establishes a foundation for longer-term treatment and recovery.

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)

MAT combines FDA-approved medications with counseling and support services to stabilize neurochemistry, reduce cravings, and lower the risk of relapse and overdose. Evidence consistently shows that MAT reduces mortality and improves treatment retention.

-

Methadone: A full opioid agonist that prevents withdrawal and reduces cravings. It requires structured dispensing, often through specialized clinics, and is highly effective for individuals with severe dependence. [6]

-

Buprenorphine: A partial agonist that alleviates withdrawal and cravings with a lower overdose risk than full agonists. Its flexibility allows outpatient prescribing and can be combined with naloxone to further reduce misuse potential.

-

Naltrexone: An opioid antagonist administered after detox to block opioid effects and prevent relapse. Naltrexone is particularly useful for highly motivated patients who wish to remain opioid-free.

MAT works best when combined with therapy, counseling, and social supports, rather than as a purely pharmacological approach.

Levels of Care

Treatment can be delivered across multiple levels of intensity, tailored to the patient’s needs, stability, and support system:

-

Inpatient/Residential Programs (30–90 days): High-structure environments offering medical supervision, 24/7 support, and immersive therapy for severe addiction or co-occurring mental health conditions.

-

Intensive Outpatient Programs (IOP): Frequent therapy sessions while maintaining daily life responsibilities. IOP allows for continued social and occupational engagement while addressing cravings, triggers, and coping skills.

-

Standard Outpatient Care: Less intensive but essential for ongoing support, combining counseling, MAT management, and periodic monitoring to reinforce relapse prevention strategies.

Therapies

Evidence-based behavioral therapies help reshape thought patterns, coping strategies, and relapse triggers:

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Identifies and modifies unhelpful thinking and behavior patterns, equipping patients with practical coping tools for stress, cravings, and triggers.

-

Motivational Interviewing (MI): Strengthens intrinsic motivation for change and helps resolve ambivalence about recovery.

-

Family Therapy: Engages loved ones in the treatment process to improve communication, rebuild trust, and provide a stable support network.

Peer Support & Recovery Capital

Participation in mutual-support groups, recovery communities, and community-based programs can reduce isolation, normalize challenges, and provide mentorship.

Developing recovery capital—the personal, social, and community resources that support sustained recovery—significantly improves long-term outcomes.

Holistic Supports (Adjunct)

Complementary approaches address the emotional, physical, and lifestyle disruptions caused by addiction:

-

Mindfulness and meditation to manage stress and reduce relapse triggers.

-

Regular movement and exercise can restore physical health, enhance mood, and improve sleep.

-

Sleep regulation techniques to counter insomnia and fatigue.

-

Nutrition support to repair deficits caused by poor appetite, nausea, or gastrointestinal dysfunction.

These practices enhance resilience, mood stabilization, and overall well-being, reinforcing the effects of formal treatment and MAT.

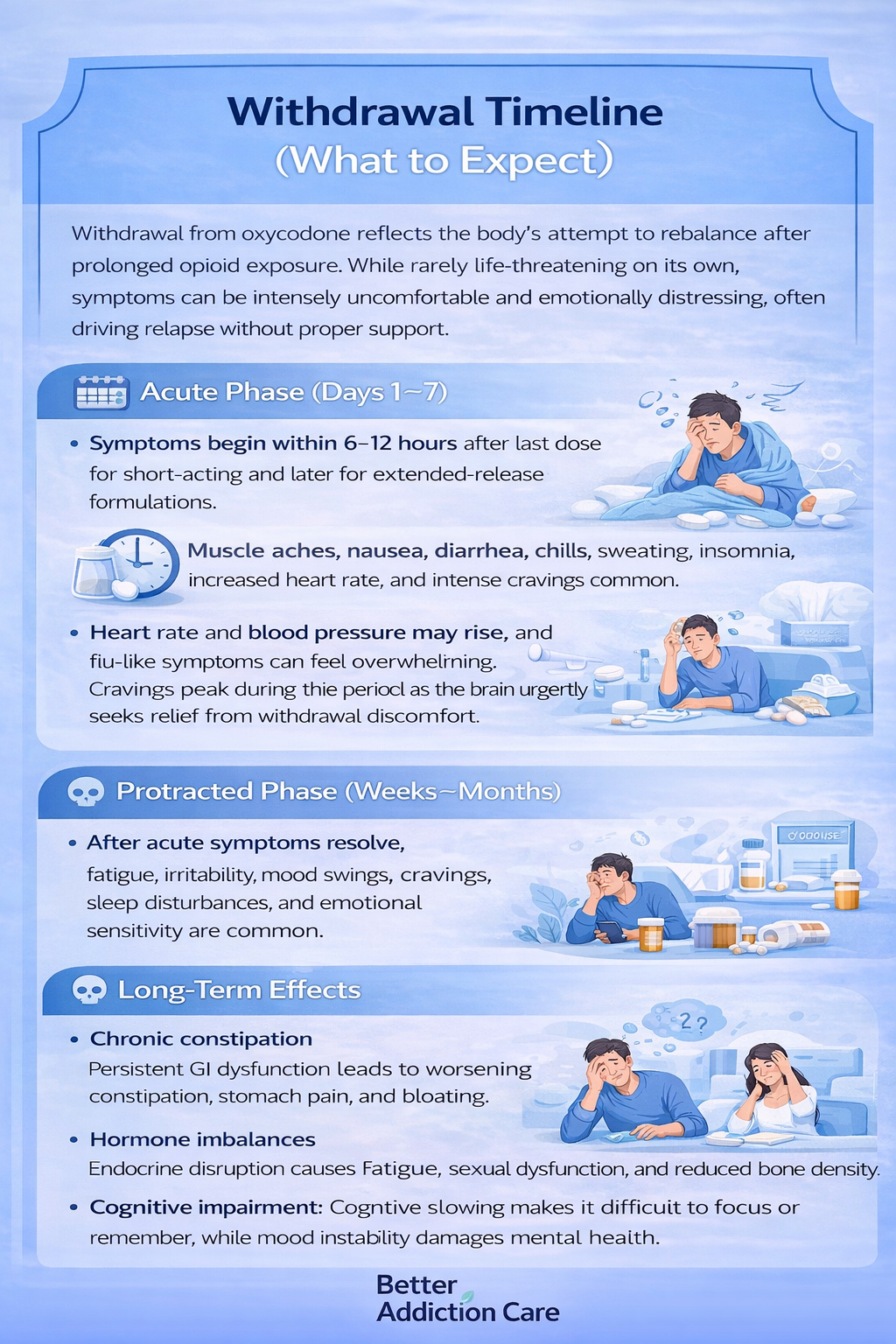

Withdrawal Timeline (What to Expect?)

Withdrawal from oxycodone reflects the body’s attempt to rebalance after prolonged opioid exposure. While rarely life-threatening on its own, symptoms can be intensely uncomfortable and emotionally distressing, often driving relapse without proper support.

Acute Phase (Days 1–7):

Symptoms typically begin within 6–12 hours after the last dose for short-acting formulations, or later for extended-release versions. During this phase, individuals commonly experience muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, chills, sweating, anxiety, restlessness, and profound insomnia.

Heart rate and blood pressure may rise, and flu-like symptoms can feel overwhelming. Cravings peak during this period as the brain urgently seeks relief from withdrawal discomfort.

Protracted Phase (Weeks–Months):

After acute symptoms resolve, many individuals enter a prolonged adjustment period. Mood swings, low motivation, irritability, persistent cravings, sleep disturbances, and heightened emotional sensitivity are common.

This phase reflects ongoing neurochemical recovery and can fluctuate unpredictably. Without continued care, these lingering symptoms can undermine confidence and increase relapse risk, underscoring the importance of long-term treatment and psychosocial support.

When to Seek Immediate Help?

Certain withdrawal-related or opioid-related symptoms require urgent medical attention. Severe vomiting or diarrhea can quickly lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, particularly in older adults or those with medical conditions.

Hallucinations, confusion, or suicidal thoughts signal a psychiatric or neurological emergency and should never be managed alone.

Overdose signs—including slowed or stopped breathing, blue or gray lips or fingertips, loss of consciousness, or unresponsiveness—require immediate action.

Emergency action: Call local emergency services immediately and administer naloxone if available. Naloxone is safe, effective, and can temporarily reverse opioid-induced respiratory depression, buying critical time until professional help arrives.

Dosing & Safety / Overdose Risks (For Legit Prescribing)

Oxycodone dosing varies widely based on formulation (immediate vs. extended-release), prior opioid exposure, pain severity, and individual metabolism.

As a Schedule II controlled substance, oxycodone carries a high risk for misuse, dependence, and overdose, even when prescribed appropriately.

High-risk combinations include alcohol, benzodiazepines, sleep medications, and other sedatives, all of which compound respiratory suppression. The primary overdose mechanism is respiratory depression, where breathing becomes dangerously slow or stops altogether—often without dramatic warning signs.

Naloxone can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose and is recommended for patients prescribed higher doses, long-acting opioids, or concurrent sedating medications.

Safe Use: Take oxycodone only as prescribed, never increase doses independently, and avoid mixing with other depressants.

Medications should never be shared, stored securely away from children or others, or unused tablets disposed of properly through authorized take-back programs.

These steps reduce both accidental exposure and diversion while protecting patient safety.

Conclusion

Oxycodone addiction is treatable, and recovery is achievable with the right support. Evidence-based care — combining MAT, therapy, and long-term follow-up — saves lives and restores stability.

Next steps:

-

Seek a professional assessment

-

Choose an appropriate level of care

-

Build ongoing support through family, peers, and clinicians

Early action reduces harm and increases the likelihood of sustained recovery.

FAQs

Yes. Even prescribed use can lead to tolerance and dependence, particularly with long-term therapy.

Respiratory depression, overdose, coma, and death — especially when combined with other depressants.

Relapse is common in chronic conditions and signals the need for treatment adjustment, not failure.

No. Medical supervision reduces complications, relapse, and overdose risk.

Learn warning signs, avoid judgment, encourage professional care, and participate in therapy when possible.

Usually not, but complications and post-withdrawal overdose risk make supervision essential.